There’s a moment every nursing educator recognizes.

A student sits in front of you—bright, hardworking, prepared. They’ve studied. They know the material. And yet, when you ask a simple question like “What would you do first?” they freeze. Their eyes dart. Their confidence evaporates. Sometimes tears follow.

That moment taught me something no textbook ever could.

Teaching nursing students isn’t just about delivering information. It’s about guiding people through uncertainty, pressure, fear, and transformation. Over the years, I’ve learned that what students struggle with most is rarely a lack of intelligence or effort. It’s something deeper: how to think, how to manage overwhelm, how to trust themselves, and how to become safe, competent professionals in a system that often demands perfection from beginners.

Here’s what years of teaching nursing students has taught me—about learning, failure, resilience, and what truly creates great nurses.

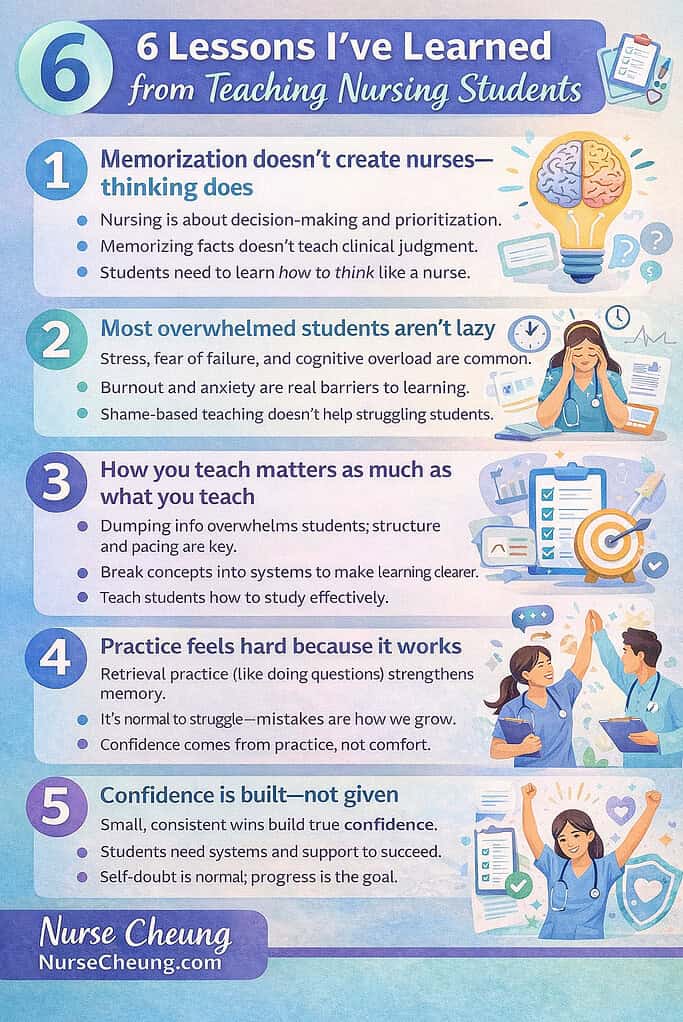

Memorization Doesn’t Create Nurses—Thinking Does

One of the biggest misconceptions about nursing school is that success depends on memorization.

Students arrive believing that if they can just remember enough facts, acronyms, lab values, and side effects, they’ll be fine. And for a while, that strategy works. Early exams reward recall. Flashcards feel productive. Rewriting notes feels safe.

Then clinical judgment enters the picture.

Suddenly the questions change. What do you do first? What matters most? What is the safest action right now? These questions don’t ask what you know—they ask how you think.

Over time, I’ve watched students with encyclopedic knowledge struggle more than students who understand patterns, priorities, and safety. Nursing is not about knowing everything. It’s about knowing what matters most in a given moment.

This is one of the hardest shifts for students to make. Thinking like a nurse means learning to tolerate ambiguity, weigh risks, and make decisions with incomplete information. That skill is learned—not inherited—and it takes time, repetition, and intentional teaching.

One of my greatest lessons as an educator has been realizing that my job isn’t to pour knowledge into students. It’s to help them organize, apply, and trust that knowledge under pressure.

Most “Unmotivated” Students Are Actually Overwhelmed

Early in my teaching career, I believed what many educators are taught to believe: if a student isn’t performing well, they must not be trying hard enough.

Years of real conversations changed that belief completely.

Most students who appear disengaged are not lazy. They are overwhelmed.

Nursing students juggle more than academics. Many are working full-time or multiple jobs. Some are caregivers. Others are navigating financial stress, language barriers, or returning to school after years away. Add the emotional weight of learning about illness, death, and responsibility for human lives, and it becomes clear why burnout is common.

Overwhelm doesn’t always look dramatic. Sometimes it looks like procrastination. Sometimes it looks like avoidance. Sometimes it looks like a student who studies for hours but can’t explain what they just read.

The brain under stress doesn’t learn efficiently. Fear narrows attention. Anxiety disrupts memory. When students feel constantly behind or afraid of failing, they stop engaging deeply—not because they don’t care, but because caring hurts.

One of the most important lessons teaching has taught me is this: compassion is not lowering standards. It’s understanding what blocks students from meeting them.

How You Teach Matters as Much as What You Teach

At some point, I realized that content coverage does not equal learning.

You can deliver a flawless lecture and still lose your students. You can assign hundreds of pages and still leave them confused. Teaching nursing effectively requires more than expertise—it requires design.

Students don’t need more information. They need structure.

They need concepts broken into systems. They need clear frameworks for decision-making. They need to understand why something matters before memorizing what it is.

When I changed how I taught—slowing down, sequencing content intentionally, reinforcing core principles repeatedly—student understanding changed dramatically. Not because they suddenly became smarter, but because the learning environment finally matched how the brain actually learns complex material.

Good teaching reduces unnecessary cognitive load. It makes the invisible visible. It gives students mental “hooks” to hang information on.

This lesson reshaped my role as an educator. I stopped asking, “Did I cover everything?” and started asking, “Did they understand what matters most?”

Practice Feels Hard Because It Works

Few things frustrate nursing students more than practice questions.

“I studied this.”

“I knew it, but I changed my answer.”

“I felt confident until I saw the question.”

And yet, practice questions remain one of the most powerful learning tools available.

Why? Because they force retrieval. They require decision-making. They expose gaps in understanding that passive studying hides.

Rereading notes feels productive because it’s familiar. Practice feels uncomfortable because it reveals what you don’t yet know. That discomfort is not a sign of failure—it’s evidence that learning is happening.

Over the years, I’ve seen countless students avoid practice because it bruises their confidence. Ironically, those same students often struggle the most on exams. The students who lean into practice—even when it feels messy—are the ones who grow fastest.

One of the most important lessons I now teach explicitly is this: struggle during practice is a gift. It’s far better to be confused in a safe environment than in front of a patient or on a high-stakes exam.

Confidence Is Built; Not Given

Students often tell me they want confidence.

What they usually mean is reassurance.

But confidence doesn’t come from being told, “You’re doing great.” It comes from evidence—small wins that prove, “I can do this.”

Confidence follows competence.

Over time, I’ve learned that my role isn’t to eliminate self-doubt. It’s to give students systems that allow them to move forward despite it. Clear study plans. Repeatable strategies. Measurable progress.

Comparison culture makes this harder. Nursing students constantly measure themselves against peers, social media highlights, and unrealistic standards. Confidence crumbles when progress is judged emotionally instead of objectively.

Teaching students to trust a process—not their mood—has been one of the most powerful shifts I’ve seen. The students who succeed are not the ones who feel confident every day. They’re the ones who show up consistently, even on days when confidence is low.

That lesson applies far beyond nursing school.

Safe Learning Environments Create Strong Nurses

Learning shuts down in environments ruled by fear.

Humiliation, intimidation, and public shaming do not produce better nurses. They produce anxious ones who hesitate, second-guess, and avoid asking questions.

Over the years, I’ve learned that psychological safety is not optional—it’s foundational. Students must feel safe enough to be wrong, to ask for clarification, and to admit uncertainty.

This does not mean lowering expectations. Nursing demands excellence. Lives depend on it. But high standards and respect are not opposites. They are partners.

When students feel safe, they engage more deeply. They take intellectual risks. They learn faster. They retain more.

One of the quiet responsibilities of a nursing educator is modeling professionalism—not just clinically, but relationally. How we correct, guide, and challenge students teaches them how they will one day treat others.

The Real Job of a Nursing Educator

After years of teaching, one truth stands above the rest: teaching nursing is not about producing perfect students.

It’s about producing safe, thoughtful, resilient nurses.

Nurses who can think under pressure.

Nurses who can admit what they don’t know.

Nurses who can keep learning long after graduation.

Along the way, teaching has taught me patience. It has taught me humility. It has taught me that growth is rarely linear and that transformation often looks messy before it looks successful.

Most of all, it has taught me that education is not about power—it’s about stewardship. We are shaping the people who will one day care for others at their most vulnerable moments.

That responsibility deserves intention, compassion, and standards that serve—not intimidate—the next generation of nurses.

A Final Thought for Students and Educators Alike

If you’re a nursing student reading this: struggling does not mean you don’t belong. It means you are learning something difficult—and meaningful.

If you’re an educator: the way you teach may matter more than you realize.

Nursing education is not just about passing exams. It’s about becoming someone capable of carrying responsibility with clarity and care.

And that kind of learning, I’ve learned, is worth the effort—for all of us.

If this resonated with you, share it with a fellow nursing student or educator who needs encouragement. And if you’re looking for structured support, study systems, or mentorship designed for how nursing students actually learn, explore more resources here on NurseCheung.com.

The journey is hard—but you don’t have to walk it alone.