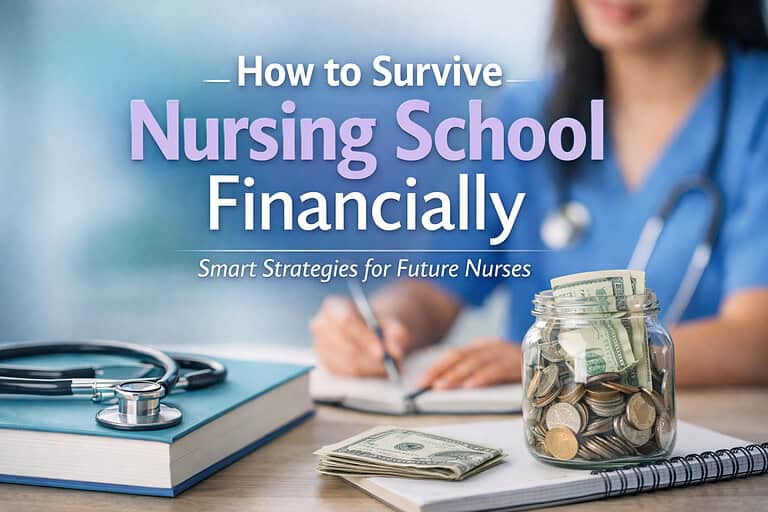

The question every nursing student quietly Googles at 2 a.m.

You’re staring at your calendar. Clinicals are locked in. Exams are stacking up. Your bank account is looking… disrespectful. And somewhere between pharmacology flashcards and care plans, the question creeps in:

Can I realistically work while I’m in nursing school?

Not “in theory.” Not “according to that one cousin who did nursing 15 years ago.” But realistically, in today’s programs, with today’s costs, and your actual life responsibilities.

This post exists to answer that question honestly—without guilt, without hustle-culture nonsense, and without pretending everyone has the same circumstances. We’ll break down what the research says, why nursing school is different from other majors, what kinds of jobs actually work, and how to tell when working is helping you survive… versus slowly sinking you.

If you’re trying to balance school, work, and your sanity, this is for you.

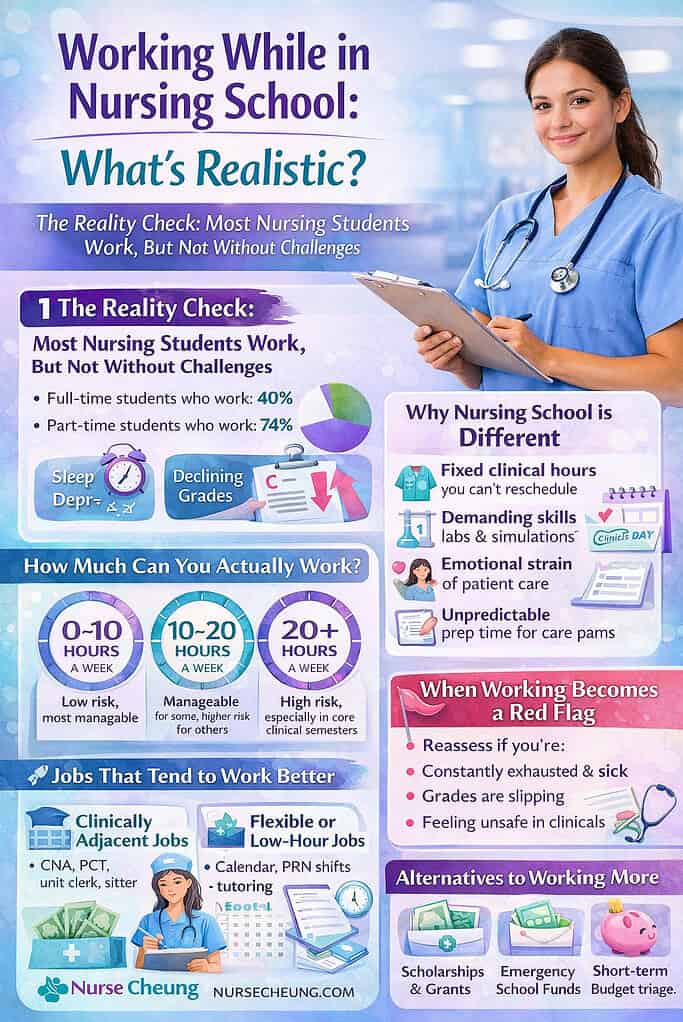

The Reality Check: Most Nursing Students Work—But That Doesn’t Mean It’s Easy

Let’s start with something important: you are not weak or “bad at time management” for needing to work during school.

National education data consistently shows that a large percentage of college students work while enrolled. For many, it’s not optional—it’s rent, groceries, childcare, transportation, and health insurance. Nursing students are no exception.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Common does not mean sustainable.

Many students do work during nursing school. Many also experience extreme fatigue, burnout, anxiety, and academic strain because of it. Both things can be true at the same time.

Working isn’t a moral failure.

Struggling while working isn’t either.

The better question isn’t “Should nursing students work?”

It’s “Under what conditions is working realistic without sabotaging success?”

Why Nursing School Is a Completely Different Beast

One reason advice about “working in college” often falls flat for nursing students is simple:

Nursing school is not structured like most majors.

Here’s why:

1. Fixed, Non-Negotiable Clinical Hours

Clinical days aren’t flexible. You don’t “fit them in.” They’re assigned, mandatory, and often long. You can’t reschedule a clinical because work ran late or you’re tired.

2. Skills Labs and Simulation

These are required, in-person, and mentally demanding. They also don’t care if you worked a double shift the night before.

3. Prep Time That Isn’t on the Syllabus

Clinical prep, care plans, medication research, chart reviews—this work happens outside of class hours and is rarely predictable.

4. Cognitive and Emotional Load

Nursing school isn’t just academic. You’re learning to care for real humans, manage high-stakes decisions, and regulate your emotions in intense environments. That kind of learning is exhausting in a way that doesn’t show up neatly on a planner.

In short: you can’t productivity-hack your way around nursing school requirements. Time and energy are the real currencies here.

So… How Much Can You Actually Work?

This is the question everyone wants answered with a clean number.

Here’s the honest version:

There is no universally “safe” number of hours.

But there are patterns.

Research on student employment shows mixed outcomes because real life is messy. Some students manage work and school well. Others don’t—and the difference usually isn’t motivation. It’s context.

That said, most nursing educators and student outcomes point to these general ranges:

0–10 hours per week

Lowest risk

Highest flexibility

Often realistic during heavy clinical semesters

Still challenging, but more sustainable

10–20 hours per week

Possible for some students

Requires strict boundaries, strong planning, and flexible employers

Risk increases during exam-heavy or clinical-heavy terms

20+ hours per week

High risk during most nursing programs

Strongly associated with sleep deprivation, declining performance, and burnout

Often manageable only in very early prerequisite phases or with extraordinary support systems

Here’s the key insight:

It’s not just about the number of hours—it’s about when those hours happen and what they cost you.

If work regularly steals sleep, study quality, or recovery time, the bill will come due.

The Hidden Costs of Working Too Much

Most students don’t burn out because they “weren’t tough enough.” They burn out because the math stops mathing.

Some common warning signs:

You study constantly but retain very little

Your sleep schedule is chaotic or nonexistent

You dread clinicals instead of learning from them

Your patience is gone—at school and at home

You’re barely passing despite enormous effort

Fatigue and burnout among nursing students are well-documented issues. Chronic exhaustion doesn’t just affect grades—it affects judgment, emotional regulation, and confidence. And in a profession built on safety and critical thinking, that matters.

Burnout isn’t a personal flaw.

It’s often a signal that too many demands are competing for too little energy.

Jobs That Tend to Work Better During Nursing School

If you do need to work, the goal isn’t “find the perfect job.” It’s:

Find the least harmful job for this season of life.

Here are categories that tend to work better than others.

Clinically Adjacent Roles

Examples: CNA, PCT, patient sitter, unit clerk

Pros:

Builds clinical confidence

Familiarizes you with hospital environments

Can reinforce what you’re learning in school

Cons:

Physically exhausting

Easy to pick up “just one more shift”

Risk of being overworked because you’re competent

These roles can be helpful—but only with firm boundaries.

Flexible or Low-Hour Jobs

Examples: weekend-only work, PRN roles, tutoring, remote or gig-based work

Pros:

Schedule control

Easier to protect study time

Lower cognitive drain in some cases

Cons:

Income may be inconsistent

Requires self-discipline to avoid overbooking yourself

Tuition-Assisted or “Earn While You Learn” Programs

Some healthcare systems offer roles designed specifically for nursing students, often with limited weekly hours and tuition support.

Why these matter:

School is prioritized by design

Hours are capped

There’s often a job pipeline after graduation

These programs model what “realistic” work looks like: alignment instead of conflict.

When Working Becomes a Red Flag (Not a Badge of Honor)

There’s a difference between pushing through a hard season and ignoring warning signs.

It may be time to reassess work if:

Your grades are slipping despite effort

You’re constantly exhausted or getting sick

You feel unsafe or unprepared in clinicals

You’re missing assignments or deadlines

Anxiety or hopelessness is becoming constant

Reassessing isn’t quitting.

It’s strategic self-preservation.

Sometimes the bravest decision is to step back before you’re forced to.

Alternatives to Working More Hours

When money is tight, “just work less” can feel laughably unrealistic. But there are often other levers to pull.

Scholarships and Grants

Professional nursing organizations offer aid that many students overlook. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing maintains resources for nursing-specific financial support.

School-Based Emergency Funds

Many programs have hardship or emergency grants. They’re underused and often under-advertised.

Budget Triage

This isn’t about perfection—it’s about survival-mode budgeting for a defined season. Temporary sacrifices now can prevent long-term academic setbacks later.

The goal isn’t comfort.

It’s getting through school intact.

What This Looks Like in Real Life

The Weekend-Only Student

Works Saturdays and Sundays, keeps weekdays for school. Tired—but predictable.

The Hospital-Supported Student

Works limited hours in a tuition-assisted role. Less money now, more stability later.

The Overextended Student

Works too much, burns out, and has to repeat a course. A costly lesson, but a common one.

The Adult Learner

Balances school, work, and family. Often needs support systems and flexibility more than motivation.

There is no single “right” path—only paths that fit your reality.

Realistic Doesn’t Mean Easy—It Means Intentional

Working while in nursing school is possible for many students.

It is also hard, draining, and deeply personal.

Realism means:

Knowing your limits

Respecting the structure of nursing education

Choosing sustainability over constant survival mode

The goal isn’t to prove how much you can endure.

The goal is to graduate as a safe, competent, confident nurse.

So here’s the question to sit with:

If nothing about your schedule changed, would it still be working for you eight weeks from now?

Answering that honestly can change everything.

If this post helped you feel seen or clarified your next step, share it with another nursing student who might be silently struggling. And remember—you don’t have to do this perfectly. You just have to do it intentionally.