Most people picture the immune system as a single invisible army that either works or fails. When we get sick, we assume it “didn’t do its job.” When we recover, we credit it with being “strong.”

That mental model is simple—but it’s also misleading.

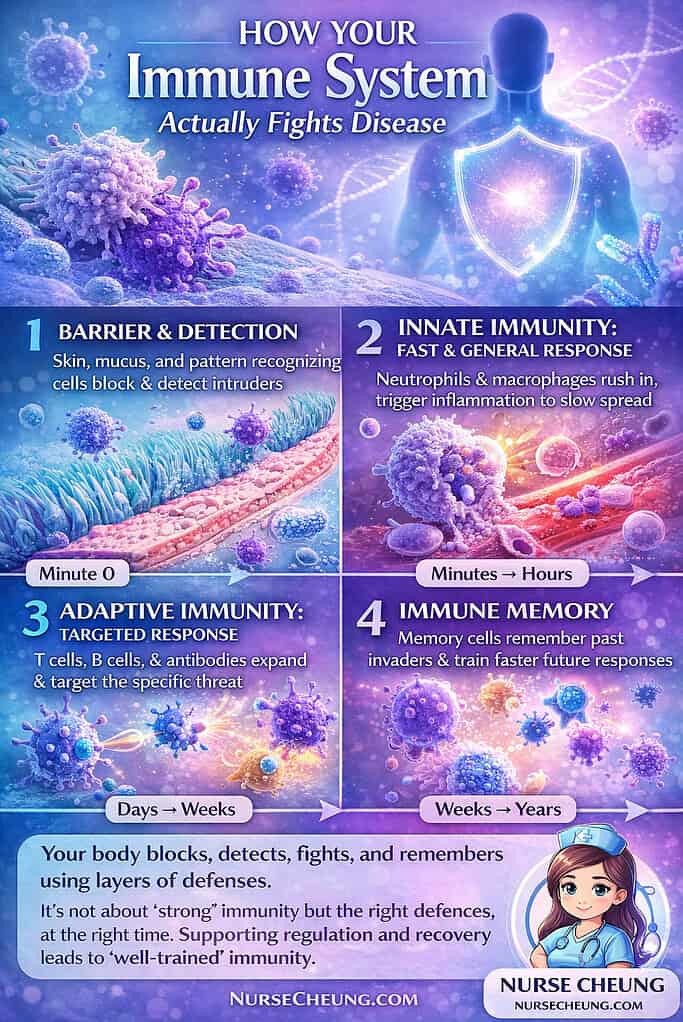

Your immune system isn’t one thing. It’s a layered, coordinated network of barriers, cells, signals, and memories working on different timelines. Some parts act in minutes. Others take days. Some respond loudly with inflammation and fever. Others work quietly in the background, preventing illness before you ever feel a symptom.

Understanding how your immune system actually fights disease doesn’t just satisfy curiosity. It changes how you interpret symptoms, illness, recovery, and even prevention. Let’s walk through what really happens—step by step—when your body encounters a pathogen.

The Immune System Myth We All Believe

The most common misconception about immunity is that it’s an on/off switch: either your immune system is “good,” or it’s “weak.” In reality, immune responses are situational. They depend on the type of pathogen, where it enters, how fast it replicates, and how well your immune system can recognize and coordinate a response.

This is why two people can encounter the same virus and have completely different experiences—one barely notices, another ends up bedridden. It’s not just about strength. It’s about timing, communication, and regulation.

To understand this, we need to follow the immune response from the very beginning—before you ever feel sick.

Step One: The Body’s First Line of Defense (Before You Feel Sick)

Most immune battles never make the news. They’re over before you even realize anything happened.

Your first line of defense consists of physical and chemical barriers designed to keep pathogens out altogether. Skin acts as a tough, continuous wall. Mucus traps microbes in the nose and throat. Tiny hair-like structures in your airways move that mucus upward and out. Stomach acid destroys many organisms before they ever reach the intestines.

These defenses are part of innate immunity—the portion of the immune system you’re born with. It doesn’t need to recognize a specific virus or bacterium to work. Its job is simple: block entry and flag danger early.

Importantly, your body doesn’t wait to identify a specific germ before responding. Immune cells recognize common “patterns” shared by many pathogens—signals that something doesn’t belong. This allows the immune system to act fast, even when it has never seen the invader before.

If a pathogen gets past these barriers, the next phase begins immediately.

The Fast Response Team: Innate Immunity in Action

Innate immunity is fast, aggressive, and non-specific. It’s designed to contain damage, slow pathogen spread, and buy time.

When immune cells detect an invader, they release chemical signals that trigger inflammation. Inflammation isn’t a mistake—it’s a coordinated response. Blood vessels widen, allowing immune cells to exit the bloodstream and reach the affected tissue. The area becomes warm, red, swollen, and often painful.

This is why inflammation feels unpleasant. It’s not subtle. But it’s effective.

Neutrophils are usually the first immune cells to arrive. They engulf pathogens, release antimicrobial substances, and sacrifice themselves in the process. Macrophages follow, cleaning up debris and continuing the fight. Together, these cells form the backbone of the early immune response.

At the same time, proteins in the blood known as the complement system activate. This system amplifies inflammation, tags pathogens so immune cells can recognize them more easily, and in some cases directly damages invading microbes.

You may also experience fever, fatigue, or body aches during this stage. These symptoms aren’t signs that your immune system is failing—they’re evidence that it’s actively working.

However, innate immunity has limits. It can slow an infection, but it can’t always eliminate it completely. That’s when the immune system escalates.

Calling in Reinforcements: How the Immune System Learns the Enemy

While innate immune cells are fighting, something more strategic is happening behind the scenes.

Certain immune cells collect pieces of the invading pathogen and travel to nearby lymph nodes. There, they present these fragments—called antigens—to other immune cells. This process, known as antigen presentation, is how the immune system learns exactly what it’s dealing with.

Lymph nodes act like command centers. When immune cells arrive carrying pathogen information, they activate specialized cells that can mount a targeted response. This is why lymph nodes often swell during infection—they’re busy coordinating.

This transition marks the shift from innate immunity to adaptive immunity, the part of the immune system responsible for precision and memory.

Precision Strikes: Adaptive Immunity Takes Over

Adaptive immunity is slower to activate, but far more specific.

Helper T cells coordinate the response, sending signals that activate other immune cells. Cytotoxic (killer) T cells seek out and destroy infected cells, preventing pathogens from using your own cells to replicate.

Meanwhile, B cells begin producing antibodies—proteins designed to recognize and bind to specific pathogens. Antibodies can neutralize viruses directly, block bacteria from attaching to cells, or tag invaders so other immune cells can destroy them more easily.

This process takes time—often several days—which is why symptoms may worsen before they improve. But once adaptive immunity is fully engaged, the immune system becomes much more efficient.

This stage also explains why antibiotics don’t work against viral infections. Antibiotics target bacterial structures; viruses require immune-mediated clearance, particularly by T cells and antibodies.

The Forgotten Front Line: Mucosal Immunity

Most infections don’t start in the bloodstream. They begin at surfaces—your nose, lungs, gut, and mouth. These areas have their own specialized immune defenses collectively known as mucosal immunity.

One key player here is secretory IgA, an antibody found in mucus and other secretions. Rather than triggering strong inflammation, IgA works quietly, blocking pathogens from attaching to cells and helping remove them before they cause damage.

This is especially important for respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. Often, whether you develop symptoms at all depends on how well your mucosal defenses work in the earliest hours after exposure.

Understanding mucosal immunity helps explain why some infections feel mild while others hit hard—and why early immune responses matter so much.

Immune Memory: Why the Second Exposure Is Usually Easier

One of the immune system’s most remarkable features is memory.

After an infection clears, some B cells and T cells remain as memory cells. If the same pathogen returns, these cells respond faster and more effectively. This is why many childhood illnesses only happen once, and why vaccines work.

Vaccines safely introduce antigens—without causing full disease—allowing the immune system to build memory ahead of time. When exposure occurs later, the immune response is quicker, stronger, and often prevents illness entirely.

Researchers have also identified a related concept called trained immunity, where parts of the innate immune system become more responsive after certain exposures. While this doesn’t create pathogen-specific memory like adaptive immunity does, it highlights how flexible and dynamic immune defenses can be.

When the System Misfires: Overreaction, Underreaction, and Disease

A healthy immune system isn’t defined by intensity—it’s defined by balance.

Sometimes the immune system overreacts, attacking harmless substances or even the body’s own tissues. Allergies and autoimmune diseases are examples of this kind of misfiring.

Other times, the immune system underreacts. People with weakened immune systems—due to genetics, illness, or treatments like chemotherapy—may struggle to fight infections that are otherwise manageable.

There are also situations where the immune response itself causes damage. Excessive inflammation can injure tissues, even as it fights infection. In these cases, symptoms may be driven as much by immune activity as by the pathogen itself.

This is why the idea of simply “boosting” the immune system can be misleading. What the body needs is not more immune activity, but appropriate, well-regulated responses.

What “Healthy Immunity” Actually Means

Your immune system is not a single force. It’s a layered defense system that blocks, detects, responds, learns, and remembers. Getting sick doesn’t mean it failed—it often means it’s doing exactly what it’s designed to do.

Healthy immunity is about coordination and recovery. It’s about responding when needed, standing down when the threat is gone, and remembering what it has learned.

When you understand how your immune system actually fights disease, symptoms become less mysterious. Illness feels less like a betrayal and more like a process—one that usually ends in repair and protection.

The immune system is working for you every day, long before you ever notice it. Learning how it operates helps you respect it, support it, and trust it.

If you found this explanation helpful, consider sharing it with someone who’s ever wondered why they still get sick—or why recovery looks different for everyone. Understanding immunity changes how we think about health, illness, and resilience.